- Tharoor's fall from grace in light of his involvement with the bidding for the Kochi franchise in the Indian Premier League (IPL) has been disgraceful. But he had it coming.

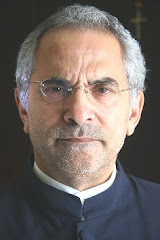

- Image Credit: AFP

Right after the Indian elections last year, like many Indians, I was excited with electing former Indian minister of state for external affairs Shashi Tharoor — an erudite, successful Indian — into power. So I wrote in this very column a year ago that we will, "usher in a new era of young, accomplished, educated and transparent politicians in India." How times change, and how the mighty fall.

Tharoor's fall from grace in light of his involvement with the bidding for the Kochi franchise in the Indian Premier League (IPL) has been disgraceful. But he had it coming.

Right from the start, Tharoor struggled with the old-world ways of the Indian political scene. As a political greenhorn who was given a Congress ticket to run from the safe seat of Thiruvananthapuram and a ministerial berth to boot, the ‘crush' on Tharoor irked many in the Congress party. Tharoor, for his part, never tried to blend in, instead preferring to seek the limelight with every opportunity.

Critics allege that Tharoor's antics since he entered politics have been characterised by a sense of superiority and entitlement. His proclivity for flippant remarks and controversial updates on Twitter irritated and embarrassed his party bosses.

They neither appreciated his temerity, nor his refusal to bend towards traditional ways nor that, as a junior minister, he continually upstaged his bosses. Politicians and observers have used several adjectives to describe Tharoor after his first year in office — arrogant, over-smart, irresponsible — but never before did anyone whisper of dishonesty or corruption. Tharoor's involvement in the IPL saga is now being attacked for what can be gross irresponsibility, at best, and stinking corruption, at worst.

Despite this, it is probably true that Tharoor is no more, or no less, corrupt than most of India's leading politicians. What makes the episode unfortunate, however, is that most educated Indians expected a man of his professional background and stature to raise the bar of probity in the shadowy world of Indian politics. The tragedy of Tharoor's fall is that those expectations have taken as hard a beating as Tharoor himself.

Mentor role

The charge is that Tharoor threw his clout behind one of the consortiums bidding for the Kochi team. Tharoor's response is that he is an MP from Kerala, that he is a cricket fan and believes that his state's youth deserve a team. And he was not part of the consortium, he says, just a mentor.

Tharoor's ambition to promote cricket in his home state is commendable, but his ‘mentoring' of the high-stakes private bidding for an IPL team is dubious. By involving himself, as a high-profile minister, in the backroom negotiations and deal-making, Tharoor has left himself open to charges of influence-peddling. The nail in the coffin, however, is the more serious allegation of corruption — that the five-per cent sweat equity awarded to his alleged girlfriend, Sunanda Pushkar, was really a kickback to Tharoor. Tharoor and the consortium deny the allegation. Pushkar, they say feebly, was hired as a marketing and PR specialist and the equity stake was in lieu of payment. Are Pushkar's skills really worth $22 million (Dh80.7million) in free equity? Tharoor seems to believe they are. He argues that if he really wanted a kickback, he would have disguised it better instead of accepting it in Pushkar's name.

Tharoor's defence is laughable. Even the most exalted marketing gurus don't make $22 million for services to be rendered in the future. And the reality is that Pushkar, a former beautician and event planner, has singularly unimpressive credentials. Despite Tharoor's silver-tongued rebuttals, it is apparent that there can really be no defence of such a massive payout to a minister's female interest.

Tharoor's followers are the educated, professional classes who have always dreamed of a leader who can conduct himself impressively and speak good English, a modern-day Nehru. To them, Tharoor will continue to provide deliverance from the earthy, rustic alternatives that India offers. To paraphrase the columnist Santosh Desai's words, Tharoor might be worried about his political future but, in a country where education and erudition is, for some peculiar reason, associated with ability and morality, Tharoor need not worry about his popularity or his Twitter following.

Rakesh Mani is a 2009 Teach For India fellow.

No comments:

Post a Comment